The Belfry Murder by Moray Dalton (Katherine Renoir 1881-1963), 1933

This is more of a thriller than a mystery. Warning: spoilers and discussion of anti-Semitism.

A gang led by a Mr X has moved on from dope-smuggling to chasing the jewels of the Tsarina, brought to England by a faithful governess. There is a lot of action on the trail of both, plus a kidnapped girl and a possibly murdered man. The writing is economical, scenes are vividly depicted, and characters are convincing. So it’s a pity that it ends up as an unresolved mess. Was Dalton up against a deadline? A word count? As well as “Good God, the swine have got Phyllis!” there is a dash of “With one bound Jack was free”.

We start off with the Borlases, father and daughter, who run a small antique shop down an alley near the London docks. Odd things start to happen. A rather deep-voiced woman comes in enquiring about Russian embroideries. The Borlases find a long-overdue letter and small, feisty Anne Borlase decides to deliver it in person. She drives to deepest Sussex and hands it to Stephen, a handsome soldier crippled in the war, and his brother, friendly chicken-farmer Martin. The letter is from Stephen's lost love, and it's all about the jewels. We settle down to follow the fortunes of Anne, Martin and the jewels, expecting wedding bells in the last chapter.

But then Anne is lured to an empty house where she is drugged by the gang, and this is pretty much the last we hear of her. The shop is ransacked and there's no sign of Mr Borlase but a large bloodstain. Martin and Scotland Yard man Hugh Collier set off in pursuit.

Now the plot becomes difficult to summarise. Anne is a mirage, always ahead of them on the road (via Arundel, Brighton etc). She survives being flung off Beachy Head by landing on one of those convenient fictional ledges. Now she’s in a nursing home, but as Martin and Collier arrive she is whisked from under their noses – in the hands of the Gang again. The action moves between the empty house (Clumber Place) and Lord Bember’s “country cottage”: a “raw new house” with white walls, "staring" red tiles and green paint, "with a large garage attached, and a hard tennis court".

Clichés abound: the rusty lock to the empty property that has been recently oiled, the weak character who pulls at their underlip, and the fellow who is “rather white under his tan”.

Enter another heroine – heiress Jocelyn, a fashionable girl, almost a Bright Young Thing. “They barge about calling each other Bunny and Baby,” someone comments. She's engaged to handsome Maurice, her father Lord Bember’s secretary and son of rich antique dealer Israel Kafka (yes really), who despite being Jewish is fond of Anne. Is it a marriage of convenience on both sides?

Anne is tracked down by a pair of bloodhounds (canine) to a rubbish pit, where she is found unconscious in a sack and is bundled off to another nursing home: The matron bent over the patient and addressed her with the brisk cheerfulness that is considered the right tone to take with the sick and dying.

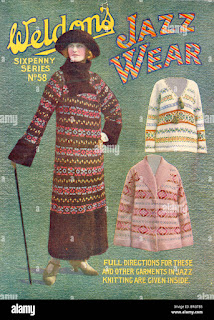

During this farrago, Martin meets Jocelyn’s brother, Lord Herbert Vaste, a weedy no-hoper studying at the vicarage with several other youths. They clearly form the Gang – you can tell by their "soiled Fair Isle jumpers" (detail for Clothes in Books). “I’ve seen them slouching about the village in jazz pull-overs and trailing scarves, with gaspers stuck to their underlips.” (A gasper was a cheap cigarette.)

Poor Bertie sobbingly confesses to Martin through a window that they forced him to throw Anne over the cliff, but they have some kind of hold over him (clearly drugs). Pathetic Bertie is incommunicado with a headache when the youths entertain Martin to dinner. Despite their constant playing of loud jazz records, they hear a single clang from the church bell and go to investigate, to find Bertie hanging from one of the bell-ropes. His recent demise is confirmed by the village's only doctor, an untrustworthy ladies’ man.

Candidates for the role of Mr X pile up: Stephen, the doctor, Mr Kafka, Maurice Kafka, Lord Bember, the vicar... Jocelyn breaks it off with Maurice, Collier and the village policeman fall into a boobytrap, the postmistress sportingly gets up at 2am to brew tea, call the doctor etc. Bedbound Stephen wrestles with, and marks, Mr X. His dog is shot but not fatally. Maurice apparently shoots himself due to a broken heart, and Mr X staggers out of a wardrobe, dying from a self-administered dose of cyanide.

The story ends with everybody telling everybody else what has just happened with a lot of paragraphs in the past perfect (had been). Will Maurice survive? Will he get back together with Jocelyn who seems to be in love with him after all? Is Mr Borlase dead or merely kidnapped? Will Anne marry Martin? Meanwhile the jewels have probably vanished on a “Russian timber ship”.

Moray Dalton was 52 when this book was written, which may account for a slightly suspicious view of modern life. The telephone had been around for several years, but there were holdouts, just as people now refuse to get smartphones or join Facebook.

“Ring me up at the Yard.” “We’re not on the telephone,” said Martin. “My fault,” Stephen’s rare smile was disarming. “It enables bores to get at one more easily, and bad news to travel faster. I prefer my fool’s paradise, without any noise-making machines.” “No wireless either, eh?” said Collier.

Later: “It’s a pity we’re not on the ’phone,” said Martin. “They are useful in emergencies,” his brother admitted.

Despite clichés, Dalton's female characters are far from the "swooning Early Victorians" mocked by Stephen – they all have grit, including the postmistress, the brothers' servant, and a cottager who gives Collier some useful background (and tea with toast and two boiled eggs).

I’m afraid fashion doesn’t feature much apart from Jocelyn’s dress with cape, Anne’s bobbed hair and Collier’s disguise as a hiker complete with khaki shorts.

The villagers were used to hikers of both sexes and expected them to stop and cry “Marvellous!” before the oldest and most insanitary cottages... Often they took photographs. In extreme cases they sat, precariously perched on folding stools, and painted pictures.

Jocelyn’s face “wore the air of faintly impertinent surprise which had puzzled him until he realised that the craze for plucked eyebrows was responsible.” She also wears an “emerald green skirt and jumper” when she should be in mourning for her brother.

On the whole the book is a glorious mishmash, sprinkled with wit and observation. One Goodreads commenter damned the book for its “anti-Semitism”, another praised its sympathetic treatment of Jewish characters.

“The Jews are a wonderful people, Anne. They have their faults, but think of the way they’ve been treated,” says Mr Borlase early on.

Lord Bember is on his second wife, and Jocelyn doesn’t approve. “I’m not interested in Beryl’s movements. Why father couldn’t leave her in the chorus—beastly little Jewess—I beg your pardon, Maurice.” “It’s all right.” His handsome dark face was a little flushed, but he answered her quietly.

Maurice opines: “There are Jews—and Jews—just as there are gentlemen and cads in every race.”

At one point Jocelyn wonders: “Why are people so beastly to the Jews? I like them.”

Maurice again: “I’m a Jew, you know. We’re supposed to be rather good at business.”

[Israel] Kafka sat for a moment, staring at the green malachite inkstand on his table. He was yellower than ever and the pouches under his eyes more noticeable... He did not move but his heavy-lidded eyes, which he usually kept half closed, seemed to film over and, from being bright, to become dull beads of jet.

Foreign eyes have peculiar powers in Golden Age mysteries. In Ngaio Marsh’s Death at the Dolphin, written in the 60s, Winter Morris (clearly Jewish) has “thick white eyelids”, and he himself refers to his “long nose”. He’s treated as one of the cast, but poor Mrs Constantia Guzman in the same book is mercilessly guyed. In Marsh’s Black as He’s Painted (70s), Alleyn's old schoolfriend Bartholomew Opala hoods his bloodshot eyes and Inspector Alleyn thinks for the first time “I am talking to a n*gro”. Poirot’s brown eyes are known to “glow green like a cat’s” when he’s on the trail, but then he’s Belgian.

Mr Kafka is rather like Agatha Christie’s large and yellow Mr Robinson, who in Cat Among the Pigeons explains his role in the world. Was he modelled on her husband Archie’s early employers?

Archie’s plans were working out. As soon as he got his demobilisation he was going in with a City firm. I have forgotten the name of his boss by this time; I will call him for convenience Mr Goldstein. He was a large, yellow man. When I had asked Archie about him that was the first thing he had said: ‘Well, he’s very yellow. Fat too, but very yellow.’ (Agatha Christie, An Autobiography)

More from Mr Kafka: A Jew may be straight or he may be crooked, but he’s very seldom a fool... Are you one of those who despise my race, Inspector? Do you talk of dirty Jews? ... If it is the diamonds you want I will give them to you if you will sign a receipt, eh? Yes”—as he saw Collier’s lips twitch—“I am a Jew—I will not be cheated even by the police.”

Our last view of him is arm-in-arm with Jocelyn as they go together to look after the wounded Maurice.